Not Infected But Still Hurting: Coronavirus’ Detrimental Social Effects

Emerging from China, the Coronavirus has spread rapidly across seas, and many nations have taken it upon themselves to block the entry of Mainland Chinese citizens into their countries. While this is to prevent a pandemic, it actually reawakens racist Chinese tropes, intensified by misinformation stemming from stereotypes.

Asian students across the nation have frequently become subjects to jokes and rumors spreading that they have the Coronavirus. It is clear these jokes are specifically targeting Asians due to the virus emerging from China. However, it is completely irrational to assume all Asians, especially those that are across the globe, catch the virus while their non-Asian peers do not. These jokes may seem harmless, however, many have admitted to feeling annoyed or hurt by the words. They are offended, but the most worrisome effect is their seclusion from others. These jokes are just a satirical cover-up of what is actually racial profiling and segregation.

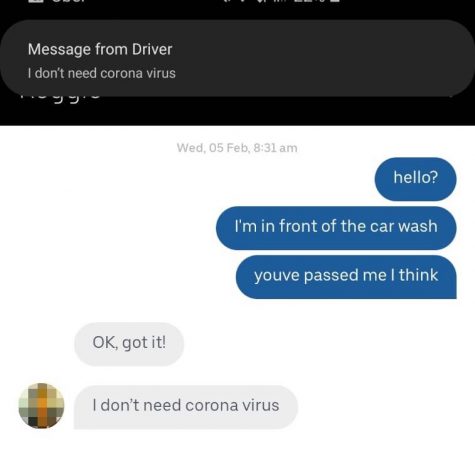

Such profiling is evident with Asian adults attempting to find jobs. The fear of the virus has especially hit hard on Uber and Lyft drivers. Many Asian-American drivers had said their number of jobs plummeted significantly over the past month. A tweet from a customer went viral, recalling their driver thanking the customer for allowing them to take the job, as others rejected them due to the virus. On the flip side, some clients have been rejected by Uber drivers due to their Asian appearance. Such has happened in Melbourne, in which the driver abandoned their Malaysian passenger at their pickup location, saying in the text, “I don’t need Coronavirus.”

Detrimental to social, financial and physical health, such profiling on Asians attacks all aspects of our lives.

However, it seems that the fear of Chinese is coming from both ends. Many in Asian countries have closed down shops, stopped going to work and school, rarely going outside to avoid contact with the virus and any people in general. It seems that the Asian community has turned on itself, icing out their own community.

There is a noticeable decrease in activity around specific Asian businesses, here in NC, especially those owned by immigrants from mainland China. Some have admitted to avoiding such businesses themselves. One Asian American student noted, “My mom won’t let us go to Grand Asia or H-Mart. She literally goes to the smaller Asian stores and once was even like ‘That one isn’t run by mainlanders.’”

Having a large Asian market, it is clear the unusual lack of customers is caused by the concern of imported produce from Asia and its Asian workers. The Coronavirus has invoked fear of anything related to Asia, notably including Asians themselves.

Maybe this issue doesn’t have to do with anti-Chinese racism, but xenophobia in general. Whenever there is hysteria, we like to point blame on a specific person or group. But with all the commotion, we must understand that the chaos actually starts and ends with ourselves.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Enloe Magnet High School, allowing us to cover our annual website costs. We are extremely grateful for any contribution, big or small!

Charlene's pass-times include: evaluating her Google Calendar color scheme, baking Tres Leches, and parking badly. Ask her, "How was your day?" and she'll...

Tony C & Tiffany K • Apr 3, 2020 at 5:03 PM

It was interesting to read and understand how the Coronavirus outbreak correlates with an increase in Asian-American prejudice and we think that the article does a great job outlining multiple examples to help support this claim. This article is by all means very well thought out and used a wide variety of rhetoric to help make this an interesting read.

However, we have some feedback and inquiries we’d like to kindly share with you pertaining to the content of the article:

This article did a great job in providing examples supporting claims about prejudice pertaining to the coronavirus, however we believe that the article can do a better job of exploring why these things happen. More specifically, Wu indicates that these examples are social effects that are caused by the coronavirus, but there seems to be a lack of how these social effects came into place to begin with. Questions like “Is this xenophobia a product of whiteness in an attempt to protect white culture?” and “Why then does that mean specifically Asian-Americans and not Italians (who also contracted the virus quickly) are being discriminated against?” are all inquiries that linger in the audience by the slight lack of explanation.

It’s natural, given coronavirus’s origins in China and the social impacts seen across the globe on Asian people of all ethnicities, to immediately assume that the cause of racism towards Asians is xenophobia, yet this claim ignores the intricacies in the relationship between sinophobia and the visible racism occurring worldwide. The usage of certain phrases, such as “racist Chinese tropes” intends to employ certain rhetoric, but by using that, Wu sets up her article to focus solely on the prejudice towards specifically Chinese people. This seems to be a contradiction, however, when her article references different Asian ethnicities, such as the Malaysian Uber passenger. This isn’t to say that this isn’t impacting these groups – it is – but Wu effectively homogenizes all people who “look Asian”. There’s no clear link explaining why anti-Chinese sentiment is affecting non-Chinese communities, such as Korean and Japanese people.

Last but not least we noticed that Wu seemed to indicate that the coronavirus “actually reawakens racist Chinese tropes” and “ doesn’t have to do with anti-Chinese racism, but xenophobia in general”. By using this rhetoric, it seemingly makes clear that the writer believes that the prejudice caused by the Coronavirus is a new awakening to dormant Asian American sinophobia, however we believe that this form of prejudice has always existed in society. With the Model Minority Myth and the exotification of Asian goods, Asian American xenophobia seems to have always remained prevalent in America, with the new coronavirus prejudice simply adding onto the already existing problem. By framing the coronavirus prejudice as a “reawakening” to Asian American xenophobia, the article mistakenly covers up many of the underlying, already existing social issues we see in this particular ethnic group.

Despite all of this, we acknowledge the effort put into writing this article. It was well done, used a plethora of examples, and pointed out the major issues surrounding racism related to coronavirus. We appreciate what is being done to increase awareness for these issues.