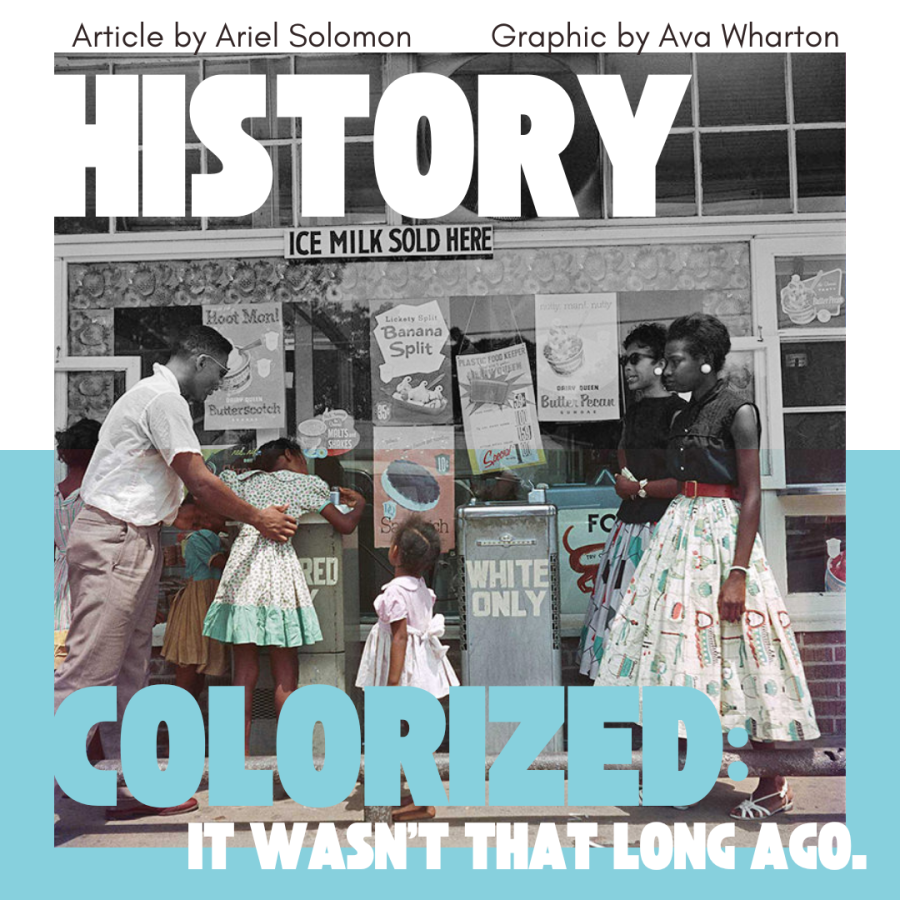

History Colorized: It Wasn’t That Long Ago

Imagine: you’re flipping through a history textbook, and land on the section on the Civil Rights movement. What do you see? Do you see an array of colors, of people with all skin tones coming together for a common cause? Or do you see different shades of black, white and gray in a grainy photograph? Most likely the latter is true, and it’s not your fault.

We have been conditioned to interpret Black history as a grayscale event, as a relic of the past. But it’s about time that we show things the way that they were, and remind people that it really wasn’t that long ago.

Color photography was invented in the 1890s by Dr. John Joly, though a commercially useful version did not appear until French brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière created the autochrome camera in 1895. Though color photography did not become widely available to the public and overtake black and white photography until the 1970s, the technique was widely practiced by professional photographers.

So from Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech to Ruby Bridges’ walk into William Frantz Elementary School, why is it that the images captured of American Civil Rights leaders appear monochrome in our textbooks?

The idea may be to keep up the guise that these events happened a long time ago, and to distance us from our history as much as possible. This development is not exclusive to photography of African American social movements, with events that happened prior to the late 90s and 2000s sharing a similar fate, as though the atrocities that our country has committed were not a mere generation away.

If you are a member of Generation Z, it is very likely your grandparents bore witness to the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the Civil Rights movement, and even lived through the Great Depression. As their descendents, we are only six generations removed from the abolishment of slavery. America has a relatively short history on a global scale, and it is immeasurably important to show that history in its proper form— the atrocities faced by Black America did not occur in black and white, nor can they be characterized as ancient history. There is an inherent psychological bias when looking at images in color versus grayscale. A group of graduate researchers at Ohio State University conducted a study to observe the differences in cognitive function when people were shown images in color and in black and white for the purposes of advertising.

They stated that “the human eye is relatively advanced in its perception of color… the fact that our environment is mostly colorful rather than black-and-white suggests that our visual experience of the environment is predominantly in color… the experience of BW imagery is psychologically removed, reflecting an experience that deviates from the colorful experience of “me” in the “here-and-now.” So, the perception of BW (vs. color) imagery is different from the reality that is directly experienced.”

Humans will always associate color with relevancy, so when we remove this factor from the educational resources through which students are exposed to history, especially Black history, it can allow a dangerous presumption to take root.

Of course, it’s difficult for us as students to change what’s in our textbooks, but there are other ways that we can properly pay homage to the Black history events we learn about. If you’re doing a project for your history class, always try your best to gather pictures that are originally in color or colorized for your presentations. Make a conscious effort to remember that every individual in those black and white images is a person like you are, who walked and talked and saw the world in color. And, of course, take the initiative to educate yourself. Remember, we cannot distance ourselves from our history. Much rather, it is our actions that continue to make it.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Enloe Magnet High School, allowing us to cover our annual website costs. We are extremely grateful for any contribution, big or small!

(She/her)

Ariel Solomon is a senior that enjoys creating in a variety of ways, but especially writing about her myriad of opinions. If she isn’t planning...