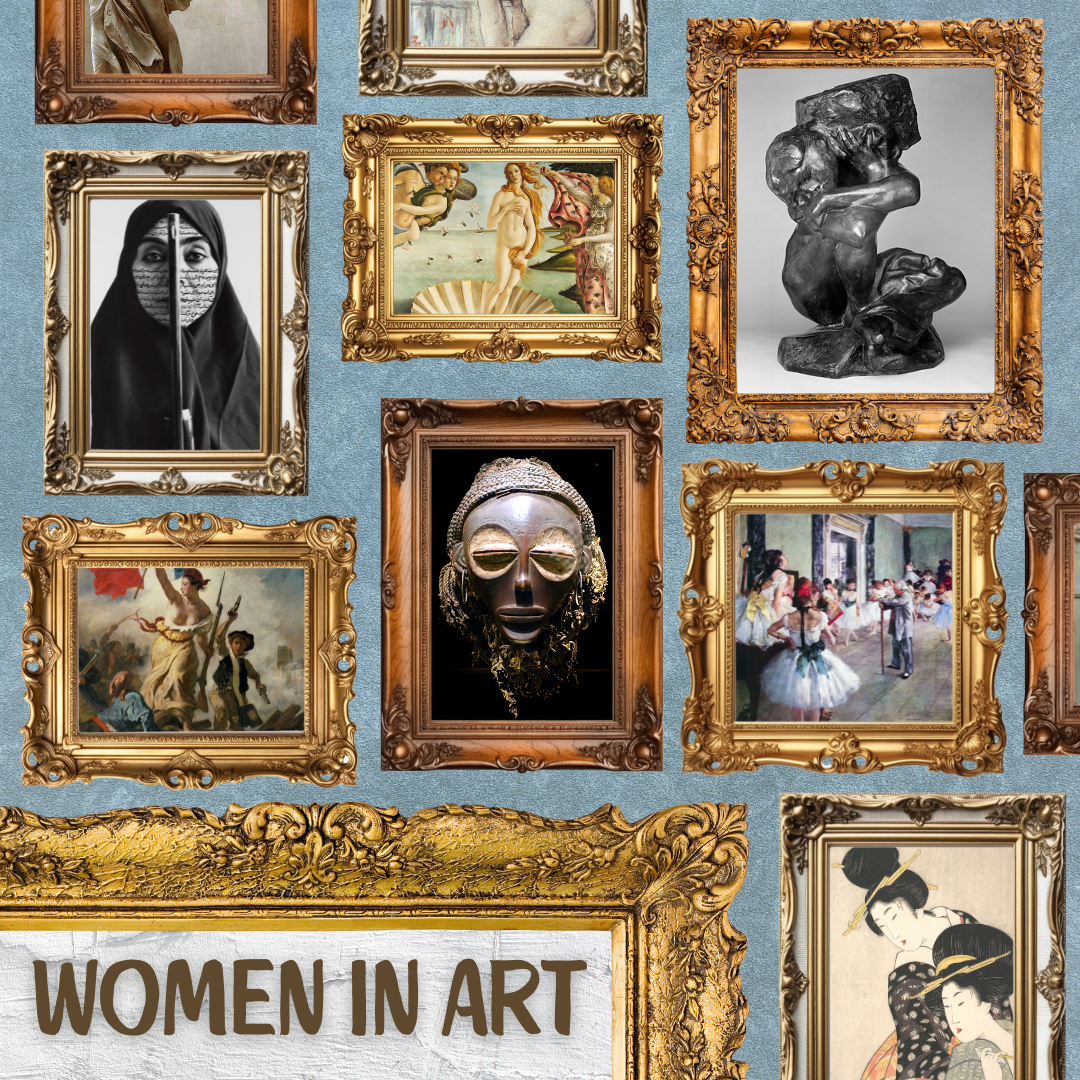

The title of “muse“ has been given to many women throughout art history, but what about the beauty of femininity inspires artists? How has the portrayal of women in art evolved over time? We have selected ten works from multiple eras and cultures to analyze how the presentation of women reflects the values of their time.

In Chronological order:

“Nike (Winged Victory) of Samthorace” (190 BC; Hellenistic)- Pythocritos son of Timocharis of Rhodes

Origin: The Greek island of Samthorace

One of the Louvre’s most treasured pieces, “Nike (Winged Victory)” most likely originated from the people of Rhodes, a Greek island. A representation of Nike, the goddess of victory, the statue stands covered in wet and windblown fabric, draping around the curves of her body: an erotized figure stepping towards the front of a ship to commemorate a victorious sea battle. The figure is restored in marble after being originally uncovered in three separate pieces, but the head and arms have never been restored. Much about the original shape, meaning, and creator of Nike is unknown, leaving her clouded in obscurity, but her feminine form is still alive in great detail, celebrating the victory of man.

“Peplos Kore”(531 BC; Archaic Greek)- (possibly) Rampin Master

Origin: Acropolis of Athens

While the figure’s posture may appear rigid, compared to the usual Archaic korai position, the stature of “Peplos Kore” sets her apart. Kore is a genre of Greek sculpture, categorized by freestanding statues, normally young women. Peplos stands with her left shoulder slightly higher than her right, and her robe falls unevenly. Her head is, very slightly, turned to the left. These small adjustments make the figure appear in a more natural, humane pose than most korai. Small hints of red remaining on the sculpture suggest vibrant watercolor originally covered the woman. Additionally, 35 holes mark the crest of her head, indicating a large wreath once graced her alongside other decorative garments. With this context, we can interpret her as a goddess, possibly Artemis. Seen as the beauty standard of her time, we can look at “Peplos Kore” and appreciate her representation of Greek women and reputation as iconic archaic art.

“Birth of Venus” (1485; Italian Renaissance)- Sandro Botticelli

Origin: Florence, Italy

An iconic, well-renowned work, “Birth of Venus” depicts Venus, or Aphrodite to the Greeks, representing beautiful femininity–not something to be gawked over, but her own entity driving the purpose of life. Venus holds the classic figural pose “Venus Pudica,” where a nude goddess covers her pubic area with her hand. She is painted with no shadow, making her appear weightless or floating. Botticelli broke barriers as the first to depict a woman (other than Eve) naked and on such a large scale. His portrayal of Venus was a rare form of the goddess as she was usually depicted erotically; Botticelli paints Venus with sloping shoulders, a small head, elongated arms, and collapsing hair, emulating the Italian beauty standard of the time.

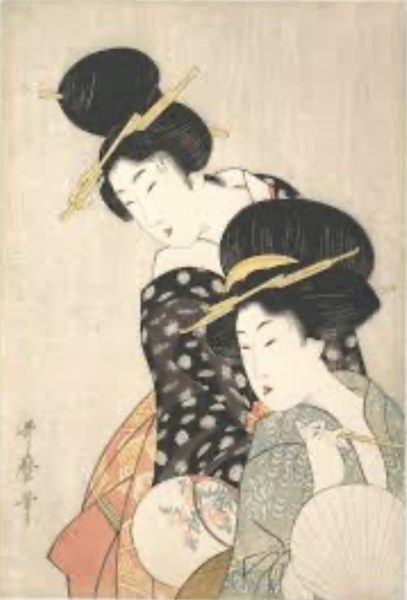

“Two Women” (1790; Japanese Edo)- Kitagawa Utamaro

Origin: Japan

Japanese woodblock printing, or Ukiyo-e, is one of the most influential art styles in the world, most famous for its Bijin-ga (beautiful women) genre. Japanese courtesans and actresses, seen almost as idols by the public, were typically the muses of Bijin-ga, shown doing daily tasks like bathing or styling their hair. These women reflected the ever-changing Japanese beauty ideals, both in their outward features (thin noses, a small mouth, and widely spaced eyes) and in their personalities (passive, attentive, and preparing to entertain male companions). Utamaro, one of the most popular Ukiyo-e artists, was one of the first to portray females with emotions and personalities, more than just an item in a painting.

“Liberty Leading the People” (1830; Romanticism)- Eugene Delacroix

Origin: France

Known as one of the founders of romanticism, Delacroix showcases a moment from the July Revolution of 1830 in “Liberty Leading the People.” He displays a woman, dress slipping off her shoulders, center frame as an allegory to the idea of freedom. No, there was not an actual half-naked woman on the battlefield, but her expressed nude ‘freedom’ emulates the faith toward freedom worth fighting for. The woman embodies these ideals by wearing a Phrygian cap, commonly given to freed slaves, symbolizing freedom across the Atlantic in the 18th and 19th centuries. By portraying female nudity, which is consistently used as a weapon against women even in the 21st century, as a symbol of freedom, Delacroix’s statement is still impactful today.

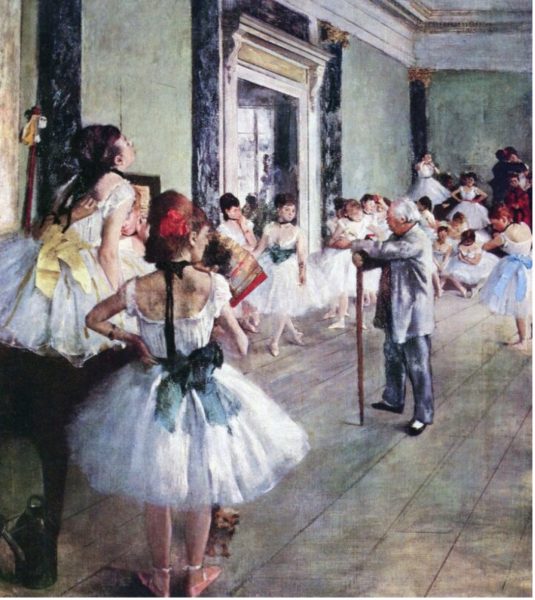

“The Dancing Class” (1874; Impressionism)- Edgar Degas

Origin: Paris, France

Ballet fascinated Degas, who frequently highlighted the art form in his works. He was specifically interested in how dancers worked behind the scenes during rehearsals and training. While he painted several works depicting Paris Opera ballerinas dancing on stage, his portrayal of the dancers in “The Dancing Class,” out of breath and human, is arguably a better representation of the beauty of ballet. Even now, ballet’s physical demands are overlooked for the end product: the effortless grace. Degas captured the unposed natural beauty of hard work, highlighting feminine grace even when a woman is not actively performing.

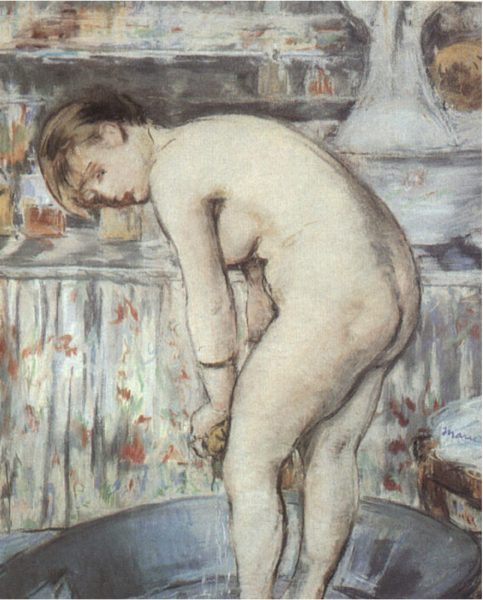

“Woman in Tub” (1878; Impressionism)- Edouard Manet

Origin: Paris, France

The presentation of women bathing was seen across multiple works of art in the 19th century, specifically in works by Manet and Degas, who had an artistic relationship that fascinates art historians to this day. This period marked the transition from the posed portrayal of mythological nude creatures to the naked form of a “realistic” woman. Manet’s portrayal is intrinsically vulnerable, specifically because of the subject’s awareness that she is being watched and in the presentation of her “imperfections.” After Manet’s death, Degas began to present women bathing in brothels (some historians believe these women were between “customers”), and the portrayal of female nudity changed yet again, perhaps losing the innocent beauty that Manet captured.

“Fallen Caryatid Carrying Her Stone” (1881; Impressionism, Modern Art)- Auguste Rodin

Origin: The original caryatids originated in Ancient Greece, but this reimagining is from Paris, France

Caryatids are most well known for their presentation as columns holding up the Erechtheion, an ancient Greek temple, and their symbolism for piety and female strength. However, after studying Caryatids for an architectural project, Rodin reimagined them. Carving a contorted female form, she is struggling under the weight of the same expected values. This caryatid is crushed under her burdens but refuses to abandon her task, exemplifying unimaginable courage. The perseverance of women is a force seen across civilizations and is extremely prevalent today.

“Mwana Pwo” Female Chokwe Mask (Late 19th century)- Chokwe people

Origin: Chokwe regions, spanning from the south of Congo to the northwestern corner of Zambia

Within the Chokwe community, young men go through a rite of passage that initiates them as men and separates them from the realm of women and children within the tribe. Masquerade characters play a major role during the initiation. One of these characters is Mwana Pwo, a female form representing ideal womanhood. Made by men out of wood, the masks are sometimes modeled after women within the tribe that the carver admires. The Mwana Pwo’s role in the initiation is to honor the mothers who raise the boys, as the masks are worn by men as well. The appreciation of women, both as mothers and partners, is a testament to the respect the Chokwe community has for femininity. This appreciation holds a tremendous amount of importance today, as discrepancies in maternal healthcare and an overall lack of acknowledgment of the sacrifices of mothers is an issue that typically falls to the back burner.

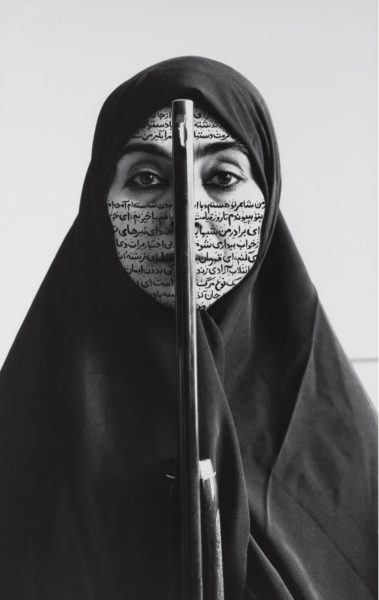

“Rebellious Silence, Women of Allah” (1994, modern)- Shirin Neshat

Origin: Created in New York, but inspired by the artist’s experiences in Iran

The “Woman of Allah” series is a series of photographs by Shirin Neshat that each feature a defining symbol of Western representation of the Muslim culture. An Iranian photographer and artist, Neshat created the series after her first visit home to Iran during the revolution. The series comments on women’s place in the Iranian conflict and how they are perceived within their religion and by the Western world. The series, and “Rebellious Silence” in particular, convey themes through the woman’s gaze, the use of Arabic mimicking newspaper clippings, and a gun dividing the picture’s symmetry. As Neshat said herself, “Every image, every woman’s submissive gaze, suggests a far more complex and paradoxical reality behind the surface.”

Art is regarded as one of the most telling artifacts of periods and cultures. During this Women’s History Month, we implore you to appreciate women’s role in art over centuries and how the beauty of femininity is inspiring in all of its forms.

Works Cited

Great Paintings- DK

Botticelli Birth of Venus | Britannica

Definition of Venus Pudica – Art History Glossary

» Eugène Delacroix, Liberty Leading the People

rodins-fallen-caryatid-is-an-entrancing-masterpiece-of-symbolism

https://smarthistory.org/female-pwo-mask/

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/120215/female-face-mask-mwana-pwo

https://smarthistory.org/shirin-neshat-rebellious-silence-women-of-allah-series/

https://medium.com/make-it-red/objects-of-beauty-women-in-ukiyo-e-prints-2edbb430580b

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/52002

https://museum.maidstone.gov.uk/representation-women-femininity-japanese-woodblock-prints/