Ernest “Ernie” Barnes was an enigma to the people around him. An art student on an athletic scholarship, a self-described outcast who was too absorbed in his sketchbook to fit in with his classmates, a Black man in a freshly desegregated North Carolina.

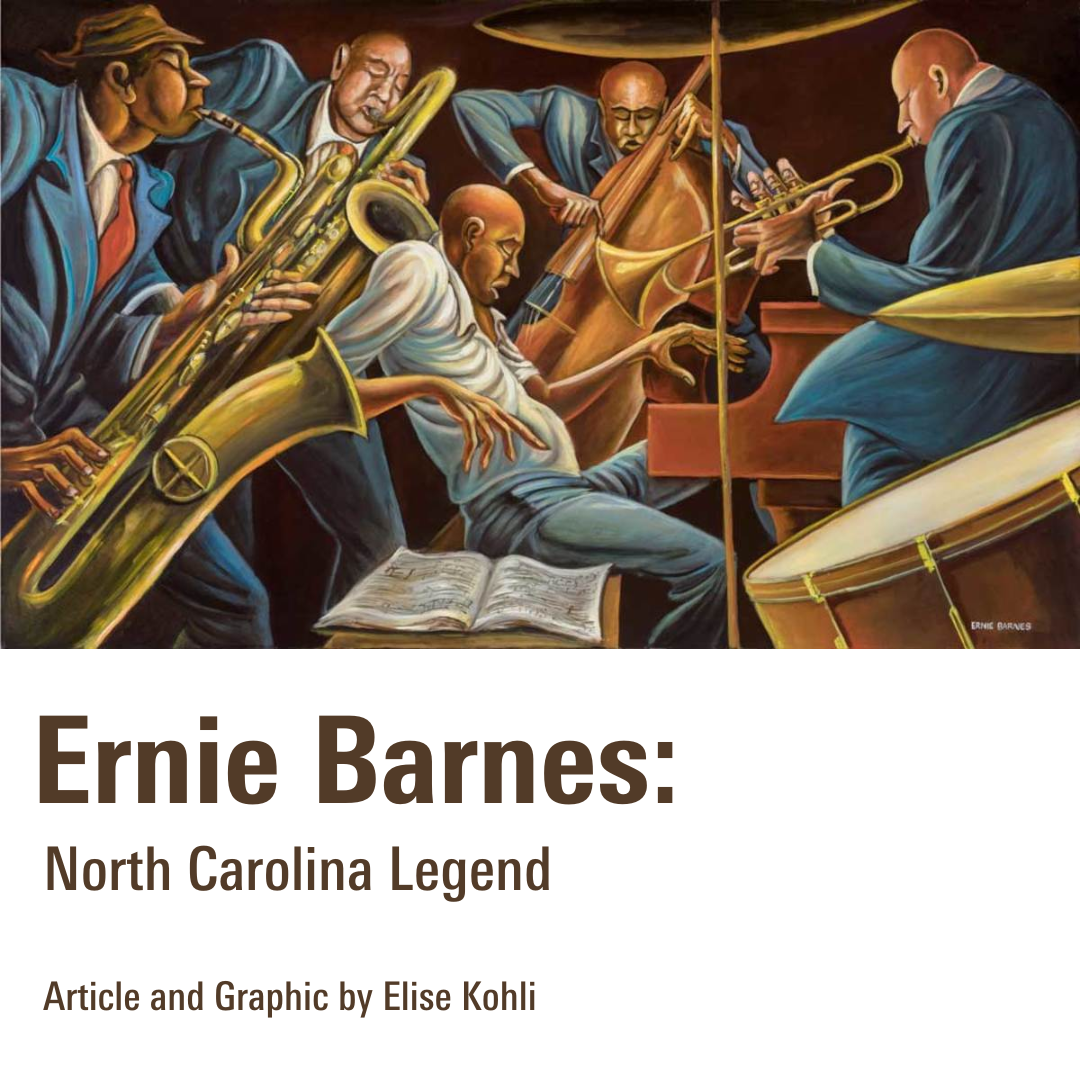

Born in “The Bottom” of Durham, Ernie Barnes was shaped by the Jim Crow south. Barnes describes his experience at a Juke Joint, a bar with jukeboxes and dancing, as a pivotal moment in his childhood. The movement he witnessed at a young age would later inspire his painting The Sugar Shack, and this obsession with capturing movement would evolve with his burgeoning career as an athlete, solidifying his signature style.

Growing up isolated because of his interest in the arts, Barnes cited his “habit of drawing” as what set him apart from his peers, but as he grew older, he described a sense of obligation to try out for the football team regardless of his lack of interest in the sport. This reluctant athletic talent would lead him to NC Central on a full athletic scholarship, although his major aligned with his passion, visual arts.

While he attended university, he would visit the NCMA with his fellow art students. Upon asking the docent where the African American art was, she would respond, ‘your people don’t express themselves that way.’ This was 1956.

Barnes graduated from Central and was drafted at first to the Washington Commanders, formerly known as the Redskins, who renounced the pick upon realizing he was Black. This left him as the Baltimore Colts tenth round pick, although he would be cut from the team late into training. During this time, he created The Bench in an emotional frenzy after watching the Colts play shortly after being drafted. He described the painting as a way to capture the feeling before it dissipated. The painting remains in his family’s collection to this day.

Barnes immediately began playing with the New York Titans, a team in a lower, more disorganized league. His time on the team wouldn’t last long; following a tragic death on the team, he would demand to be released. This traumatic and pivotal event in his life would lead to the creation of The Wake, a painting depicting the Colt’s coach walking across an empty stadium. As always, his community informed his subject matter; the scenes around him were what made it to the canvas.

As Barnes’ artistic talent grew, he would play on multiple different teams throughout the American and Canadian football leagues. He would draw direct inspiration from the games, sketching on the sidelines and capturing the rhythm and lines of the figures in front of him. The movement was what captivated him. His teammates would come to nickname him “Big Rembrandt.”

In 1966 Barnes would quit football, and it was then his prominence in the art world started to rise. Following his retirement, musicians began using his art for album covers, most notably Marvin Gaye’s I Want You and Curtis Mayfield’s Late Night DJ. Barnes would hold his first solo showing, sponsored by the NY Jets owner Sonny Werblin, in NYC in 1966 and it wasn’t long before his exhibition, The Beauty of the Ghetto, would tour America. There were 35 pieces, and the overwhelming message behind the works was that of Black pride.

Barnes had a homecoming of sorts in 1971 when he held a solo exhibition within the North Carolina Museum of Art. Throughout the rest of his life, Barnes would receive continuous recognition for his contribution to the culture, including the University Award, a prestigious honor by the University of North Carolina Board of Governors. He passed in 2009, but just 14 years later, the NCMA would obtain and instate his piece, The Last Hurdle, as part of their permanent collection. As the subject clears his final obstacle, 67 years after his first time at the NCMA, Barnes too has proved that docent wrong and cleared the last hurdle.

Sources:

https://www.erniebarnes.com/about

https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/30/arts/design/ernie-barnes-artist-ortuzar.html

https://www.nytimes.com/1984/05/07/sports/ernie-barnes-an-athletic-artist.html